Metric as Mediator: Data-driven negotiation over Heathrow’s Noise Landscape

(Ortner, F.P., 2017. Metric as Mediator: Data-Driven Negotiations about Heathrow’s Noise Landscape,

in: The Noise Landscape. nai010 Publishers, pp. 215–226.)

https://www.nai010.com/en/publicaties/noiselandscape/130534https://www.thenoiselandscape.com/

Heathrow’s noise landscape is uniquely contentious: as the most urban of Europe’s hub-airports there has been controversy since the creation of the airport over the effect of aviation noise on local communities. Negotiation over Heathrow’s noise landscape has sought to balance the pragmatic concerns of flight, the economic benefits of the airport to the UK, and disruption to the lives of local residents. Quantification of noise as data has been, since the 1960s, the mediator that permits negotiations over sound to occur. Mappings of noise contours, clusters of complaints and reams (now petabytes) of other data have allowed the airport operator, the UK government, and local communities to communicate and negotiate their positions relative to the noise landscape. As we will see, however, data has imperfectly mediated the experience of noise on the site. Invariably, distortion or bias has been introduced during the collection, processing, and dissemination of data. Today, new technologies for urban sensing and data-sharing are coming into use, and long-standing policies on noise at Heathrow are evolving in response. Despite these changes much of the policy shaping Heathrow’s noise landscape is strongly influenced by the first efforts to measure and map noise disturbance in this territory.

The first quantification of Heathrow’s noise landscape: the Wilson Report on Noise, 1963

Heathrow’s noise landscape was first quantified and mapped in the 1960s in response to a crisis over the disruptive noise of new civilian jets. Compared to earlier propeller planes, new jets like the Boeing B707 produced a louder and higher frequency ‘screaming’ noise that traveled greater distances.[1] Combined with a rapidly increasing number of flights moving through the airport, the Heathrow territory was experiencing unprecedented levels of noise by the late 1950s. In 1959 protest against aircraft noise crystalized around the Noise Abatement Society (NAS), founded by John Connell. Connell was moved to action by an alarming increase in complaints mailed in to newspapers about noise, in which the new aircraft were frequently mentioned.[2] Under Connell’s leadership the NAS led a series of noise protests; the most notorious of which was held at 2 a.m. in front of the home of Aviation Minister Duncan Sandys to protest the recently instituted night flights at Heathrow. In response to petitioning from the NAS the parliament passed the Noise Abatement Act of 1960, instituting new controls on noise in general throughout the UK. However, in a shocking setback for the communities surrounding Heathrow, the Noise Abatement Act upheld a prohibition on legal action for nuisance arising from civil aircraft. This restriction was justified as a necessary protection for the British aviation industry.[3] Without legal recourse, the residents of the Heathrow villages were helpless to influence the ever-increasing level of noise enveloping their communities. In compensation the Minister of Aviation recognized an obligation to ‘take steps to minimize the nuisance’ from aviation noise.[4] A first step toward the fulfillment of this obligation was the appointment of a committee to study England’s noise problem with an emphasis on Heathrow. The so-called ‘Wilson’ Report on Noise, named after the chairman of the committee, was presented to Parliament in 1963 and addressed the problem of aviation noise at Heathrow first through social research on noise impacts and second by suggesting policies for mitigation.

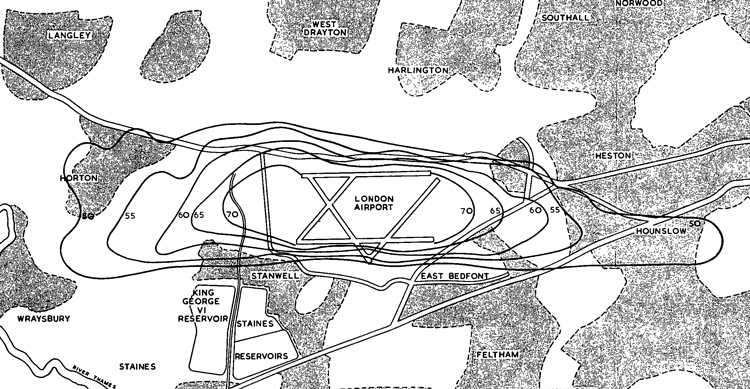

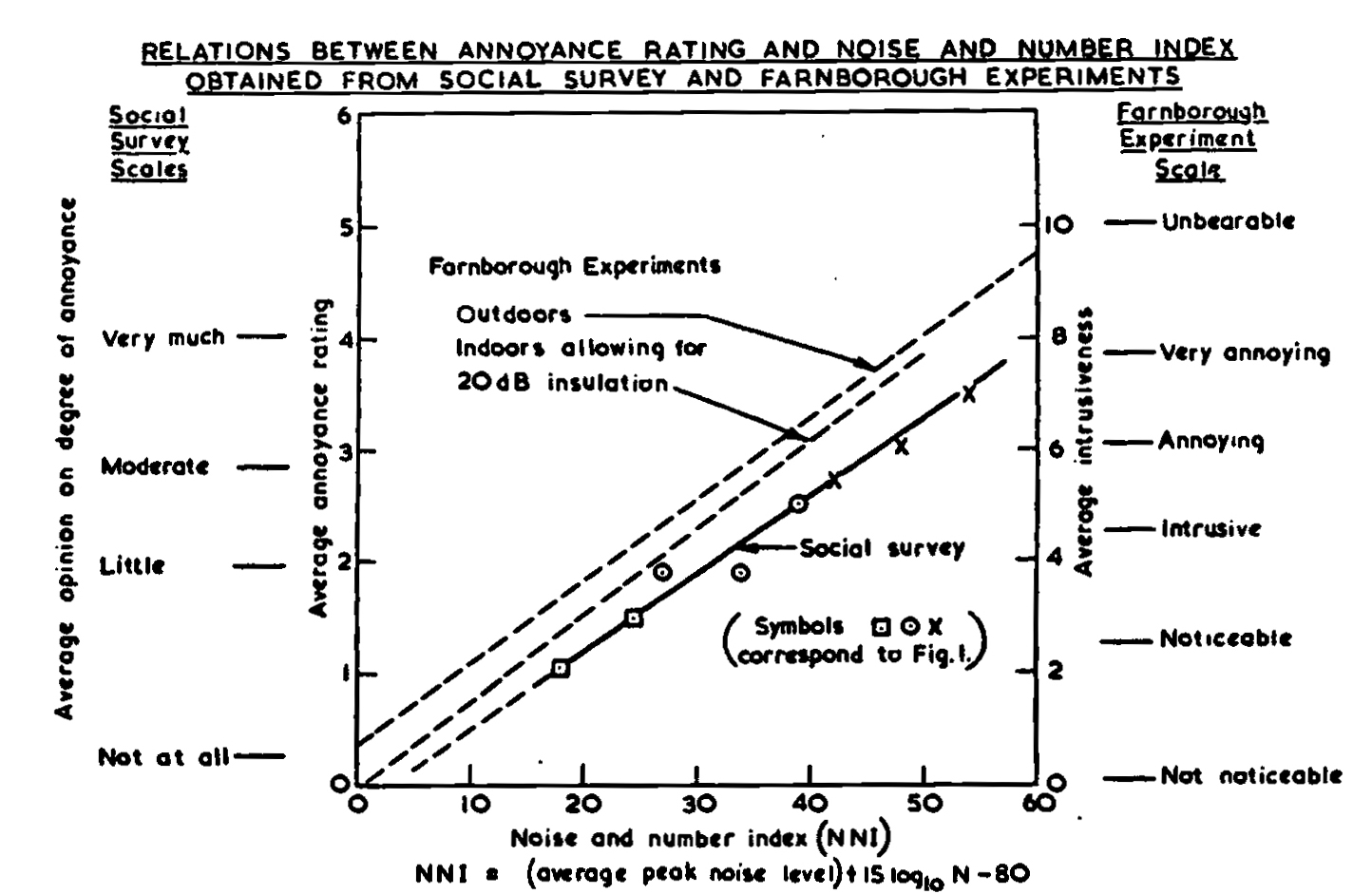

The Wilson report created the first noise quantifications and maps of the Heathrow noise landscape. The authors of the report visited the Heathrow site, surveyed its residents, and reviewed what records existed. They noticed that noise complaints had increased at the end of the 1950s at the time of the introduction of the new jet airliners and continued to increase in proportion to the growing number of flights.[5] This observation led them to assume that noise disturbance was proportional to both the noise level of flights and to their frequency. Based on this assumption they invented a new noise disturbance metric, the Noise and Number Index (NNI), which averages out the noise and number of aircraft overflying a geographic point for a specific period of time[6]. NNI represents an early predecessor of the LAeq metric used today. They then applied this index to the territory, interpolated the data points they had, and drew the first noise contour map of Heathrow for the year 1961.(fig.1) In comparing the noise contours to the number of complaints received from different areas they came to the conclusion that 50 to 60 NNI was ‘the critical range above which annoyance becomes intolerable.’[7](fig.10) This mapping technique also permitted the creation of a projected noise contour map for ten years in the future (1971), which predicted the severity of the noise problem as flight numbers increased. With these new maps in hand, the authors of the Wilson report turned to the problem of mitigating noise nuisance.

A first effort at noise mitigation through the modification of jet engines had mixed results and seemed insufficient to the magnitude of the problem. The study found that the addition of noise suppressors to the jet engines resulted in some mitigation of noise, though they did little to change the whine of compressors during landing.[8] Changes in flight procedure also resulted in some noise mitigation, with steeper take-off trajectories limiting the area impacted by noise. Aircraft of the time were unable to safely deviate from a three-degree approach angle, which meant that areas under the Heathrow approach path could expect little relief from changes in flight procedure. In spite of these efforts to mitigate aviation noise at its source the Wilson report found that, ‘there are many dwellings so near to London Airport that it is impossible to reduce the noise at particular inhabited locations to levels which most people would find reasonable.’[9] The committee concluded that Heathrow’s noise contours would continue to expand through the sixties and beyond no matter what noise suppression technology was applied to jet engines. They came to the pragmatic conclusion that if people were to continue living in the Heathrow territory they would need to be shielded in some way from aviation noise.

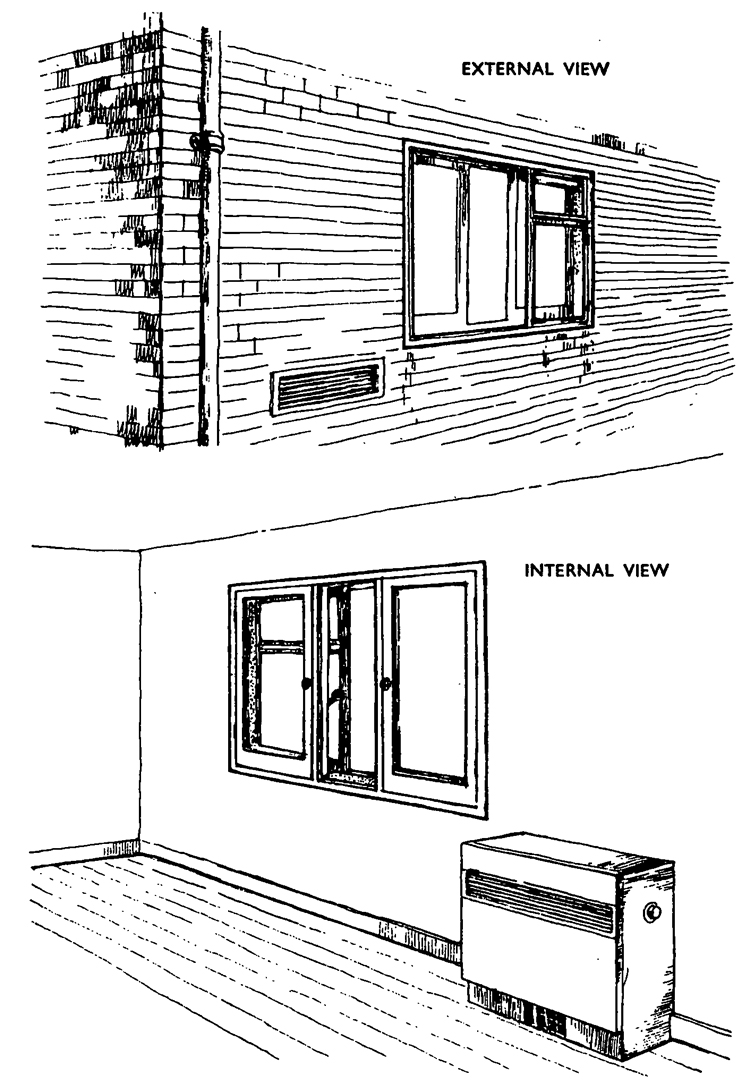

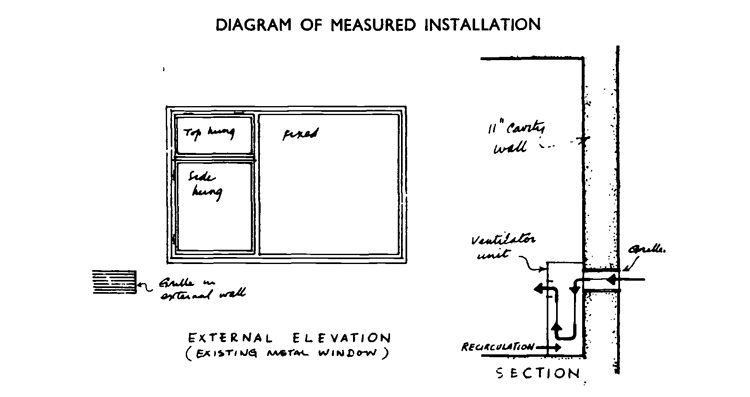

Working to mitigate aviation noise in residential neighborhoods, the Wilson report established a building research station to test modifications that might be made to existing homes.[10](fig. 7,8) Evidence collected from medical experts and the community suggested that noise disturbance was more acute at night when residents were sleeping. It was thought that modifying home construction to reduce noise would at least protect this one sensitive period of time. At the research station a series of experiments were run comparing standard single windows to new double windows combined with noise-dampening ventilation systems. The researchers found that a noise reduction of 40 dB could be achieved using a combination of these two techniques: an increase of 20dB over the standard assembly.[11] The Wilson report concluded that a policy of insulating of homes in the Heathrow area was, ‘the only practicable means of ameliorating the lot of those who are subjected to excessive noise.’[12] This recommendation made it necessary to decide how home insulation would be financed and who should be eligible. To decide these questions, the authors of the report returned to the new noise metrics they had just created, and proposed using them as thresholds for the implementation of noise insulation grants.

The Wilson Report suggested that to be eligible to receive a grant for home insulation residents around Heathrow should live within the critical 50/60 NNI contour. The NNI metric, originally an approximate designation used to study the phenomenon of noise disturbance, was thus re-applied as a policy threshold making it possible to implement the home insulation grants in spite of limited resources. Though a pragmatic solution, in retrospect the fairness of excluding individuals from the insulation grants based on what even the Wilson report acknowledged was an approximation is at least questionable.[13] A further complication resulted from the use of a metric developed for urban study as a designation for implementing urban policy. By implementing a policy on home insulation within an NNI contour, the authors of the report were fundamentally altering the way noise disturbance was spatially distributed within the noise landscape. This would contribute to decoupling the NNI metrics from the community’s actual experience of aviation noise. In the second survey of noise disruption at Heathrow, conducted in 1967, it was found that community attitudes toward noise were ‘hardening’; a possible indication of this sort of complex feedback between social research and social policy.[14] Given the constraints faced by the Wilson report committee in the early 1960s, the pragmatism of their approach to the noise problem is evident. While the continuing implementation of many of these policies in only slightly modified form is a testament to this pragmatism, we will see that it does not imply that these policies are not subject to criticism. Changing technologies combined with pressures for the expansion of Heathrow make it timely to reconsider the metrics and policies the Wilson report first proposed. Are there better ways to measure sound disturbance, and can more equitable policy for noise mitigation near Heathrow be put into place?

Noise management and monitoring technologies

The inadequacy of the noise contour as a means of facilitating communication between airport and community about noise events was acknowledged by the British Government in the Aviation Policy Framework of 2013. While noise contours do predict areas where inhabitants are more likely to be annoyed by aircraft noise, the report emphasizes that the contours have little relevance to the disturbance of one individual by the noise of one or several flights. The document goes on to state, “the Government encourages airport operators to use alternative measures which better reflect how aircraft noise is experienced in different localities […] The objective should be to ensure a better understanding of noise impacts and to inform the development of targeted noise mitigation measures.”[15] For example, instead of relying on noise contours the community would be able to access, ‘online information showing aircraft flight paths, heights and noise, track-keeping, performance reports and metrics.’[16] These exhortations, combined with the possibility of a third runway at Heathrow once again raised by the Airports Commission in 2015, have given the operators of Heathrow great incentive to be innovative, transparent and generous in sharing noise data with local communities.

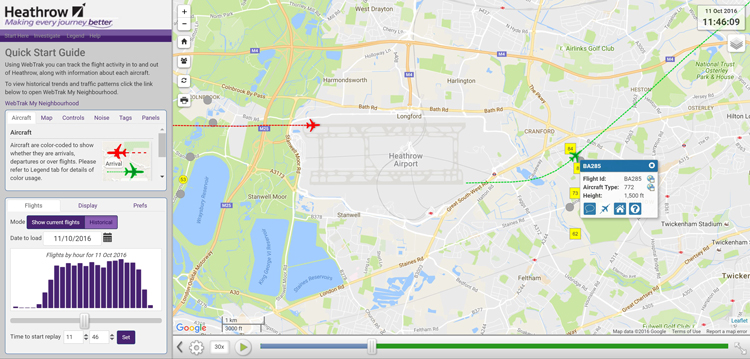

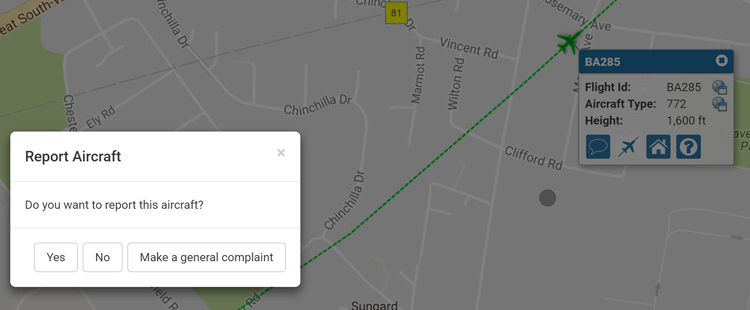

In seeking to meet evolving government expectations for noise monitoring, Heathrow has begun exploring several new ways of sharing noise data with the community. Starting in 2014 Heathrow made available on its website an aviation noise tracking software developed by Danish engineering firm Brüel & Kjær (BK), called WebTrak.(fig.3) The site displays an animation of flights arriving and departing from Heathrow, permitting access to flight number, aircraft type, altitude and speed at a chosen moment for a chosen flight. Selecting a flight also makes it possible to show the point of closest approach to a given address, and allows a noise complaint to be filed. However, the software currently shows flights with twenty minutes of delay, making real-time visualization impossible and complicating the process of filing a flight-specific complaint. To avoid the time-lag local noise forums recommend using free publicly available websites like flightradar24.com that track flights in real time. Complaints can then be made via email or telephone, entirely bypassing WebTrak.[17] It is significant that flightradar24.com provides this service by gathering its data from a group of ‘aviation professionals and enthusiasts’ that have installed self-made ADS-B sensors in their homes and networked them over the internet.[18] Noise data, in contrast to flight path, has not yet been crowd-sourced but BK has built into WebTrak the ability to show data from noise monitoring stations parallel to flight movements.(fig.5) Unfortunately, data from Heathrow’s noise monitoring stations is currently posted with a delay of about twenty-four hours, making confirmation of noise events difficult for members of the local community. When real-time aviation information is available elsewhere (and assembled by a networks of amateurs) many will wonder why the public should still rely on the airport for data on noise.

The policy of tasking the airport with collecting its own noise data originated with the Wilson report in the 1960s. At this time noise data was collected by an airport employee sitting at the end of the runway and manually recording sound levels for each arriving or departing flight. The report already mentions attempts to automate this process.[19] Today, though the noise contours for Heathrow are separately commissioned by the Department for Transport, the information accessed through WebTrak is provided directly by the airport operator, much as was the case during the Wilson report. In the interim, however, there have been important changes in the ownership and management of the airport. In the early 1960s Heathrow was a government-operated infrastructure; for the airport operator to collect and publicize noise data was a disinterested action in the public service. Heathrow has since been privatized, first as a for-profit British company named BAA, and since 2006 as a holding of an international consortium now known as Heathrow Airport Holdings Limited. The possibility of a conflict of interest, absent at the time of the Wilson Report, now exists between the obligation of the airport to generate profit for its share-holders, and its responsibility to disinterestedly collect and disseminate noise data.

The possibility of bias in noise information provided by Heathrow, and suspicion on the part of the local communities, led in 2014 to the formation of the Heathrow Community Noise Forum and a third-party vetting of Heathrow’s noise data.[20] While this vetting concluded that data presented in Webtrak was accurate and complete it did not address delays in sharing data. Concerns over the presence of bias are particularly serious for data used to construct future projections of the noise landscape. It was for just such a projection that BAA was accused in a 2008 Sunday Times article of colluding with the British Department for Transport to reverse-engineer data in order to minimize projected environmental impacts of the third runway at Heathrow.[21] Given the potential conflict of interest and the contemporary ubiquity of urban sensing it would seem timely to reconsider what institution it is best to entrust with the responsibility for sharing Heathrow’s noise data. The independent aviation noise authority proposed by the Airports Commission in 2015 could be a possible candidate for this responsibility, but it might just as easily be handled by local volunteers maintaining an independent array of sensors.[22]

Noise and urban realm

A second legacy of the Wilson report that merits re-evaluation is the policy of relying on insulated interior environments to make the areas closest to Heathrow livable. This policy was first formulated in response to the effects of aviation noise on public health that were beginning to be understood at the time of the Wilson report and have been increasingly well-established since. The population-wide impacts of aviation noise on sleep, on learning in schools and patient health in hospitals have all been the subject of study. In each case the detrimental effects of aviation noise have been repeatedly demonstrated.[23] At Heathrow the policy first proposed by the Wilson report is still in force: homes within a certain noise contour have a right to receive subsidies from the airport for noise insulation. Similarly, government policy dictates that schools and hospitals within certain noise contours will be insulated at the cost of the airport. The consequence of these public-health oriented policies, however, is community-wide reliance on sealed interior environments at night as well as day. Life in the open air is put at a lower priority, and little thought is given to what consequences noise may have here.

There is a general understanding that public space near Heathrow is not of the same quality as public space elsewhere.(fig.9) This is expressed, for example, in the open space strategy for the borough of Hounslow which observes that residents near Heathrow in neighborhoods like Cranford tend to travel more often by car to access open space for recreation.[24] To what extent noise from the airport impacts the use of public space is difficult to establish, but an anecdote from a local school suggests that it significantly modifies patterns of social contact in exterior space.

In 2011 administrators at Hounslow Heath School, directly under the approach path to Heathrow, became concerned about the disruption aircraft noise was causing to the students’ outdoor playtime and learning. One account claims that at peak times the play area is overflown every sixty seconds, and that the noise for each flight lasts on average thirty seconds.[25] School administrators and Hounslow city council members supported their concern with findings from psychological studies that demonstrated developmental delay in students attending school in areas heavily-affected by aircraft noise.[26] In response to this challenge, school administrators developed a strategy for shielding exterior areas from noise with a series of open-air adobe domes.(fig.4) The domes block and dampen noise coming from overhead while still permitting an open-air experience for playing and learning. Heathrow contributed in part to the financing of the adobe huts, and after an apparent success has committed to fund the construction of huts at twenty-one other local schools, with an additional eight being built by 2016.[27] The success and expansion of the adobe huts program raises further questions about the impact of aircraft noise on community-wide public space. What can be done to protect public space, and is shielding a viable solution?

A first criticism of the insulation program is fairly self-evident: though insulating homes and sensitive buildings mitigates some of the major public health impacts of aircraft noise, it fails to address negative impacts on open public space. Secondly, the policy of shielding of outdoor public space through, for example, adobe huts cannot produce public space of the same quality as in noise-free areas. A third criticism, however, concerns the scalability of policies seeking to mitigate noise impacts on exterior space and specifically the policy of shielding. This policy, represented by the adobe hut program, shows its limitations when we consider the impossibility of extending the policy from a few playgrounds to public space in general. If even a fraction of community-wide public space around Heathrow is to be protected from noise disturbance a different approach is necessary.

In response to the large-scale inadequacy of the shielding approach, which can only work in a very limited way, there are emerging signs of a complementary holistic approach that would be developed at a territorial scale. This approach addresses the public space of the territory at the same time as the flight paths over the territory, modifying both together instead of separately. Recent government reports suggest that expansion at Heathrow would be combined with ‘noise envelopes’ and periods of respite. [28] These suggestions represent steps in the direction of territorial scale planning that could better protect public space. The ‘noise envelope,’ however, is generally defined with little geographic specificity. It often refers only to capping the area of land or number of people contained within an LAeq contour of variable shape. For a noise envelope to contribute to holistic open space strategy, it would need to control to some degree the shape of the noise envelope both temporally and spatially. Using policy to design the shape of the noise envelope would make it possible to plan a configuration complementary to open public space on the ground.

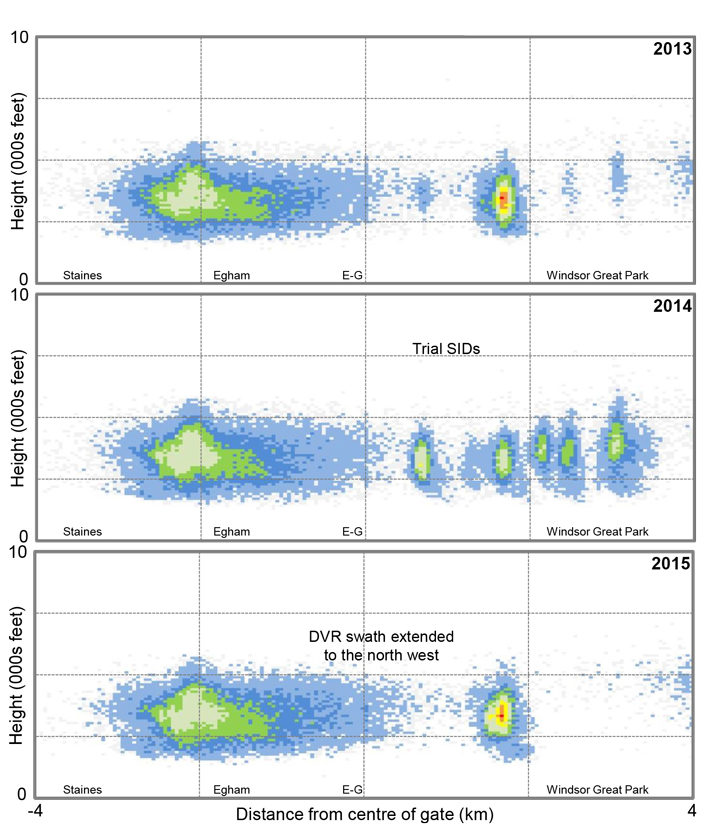

Experiments with the design of the airspace over Heathrow are already going on: in 2014 the airport ran trials of different patterns of concentration and dispersal of flights along Noise Preferential Routes (NPRs).[29] The NPRs are 3km wide corridors established in the 1960s to help mitigate aviation noise by concentrating the flow of flights within the airspace. Heathrow experimented with directing flights in different formations along the centerlines of the NPRs producing different concentrations of noise. Comparing, for example, flight paths over Englefield green and Windsor Great park: a tight cluster of flights present in 2013 appears to split into five smaller clusters in 2014.(fig.6) In 2015, after the trial has ceased, the larger cluster reappears. While the dispersal of flights evenly across the territory may share the noise burden more equitably, it is not necessarily greeted with enthusiasm by residents. Heathrow’s 2014 airspace experiments provoked confusion and resentment in some communities, particularly where over-flight increased and prior outreach was inadequate.[30] A massive effort to engage and understand the needs of people living in affected areas would be needed to effectively design airspace in complement to the urban realm.

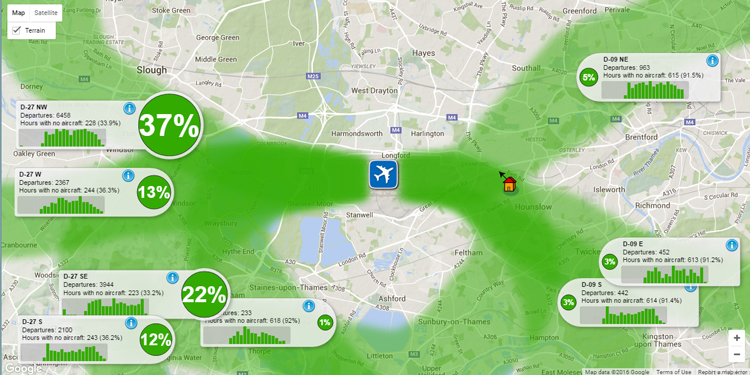

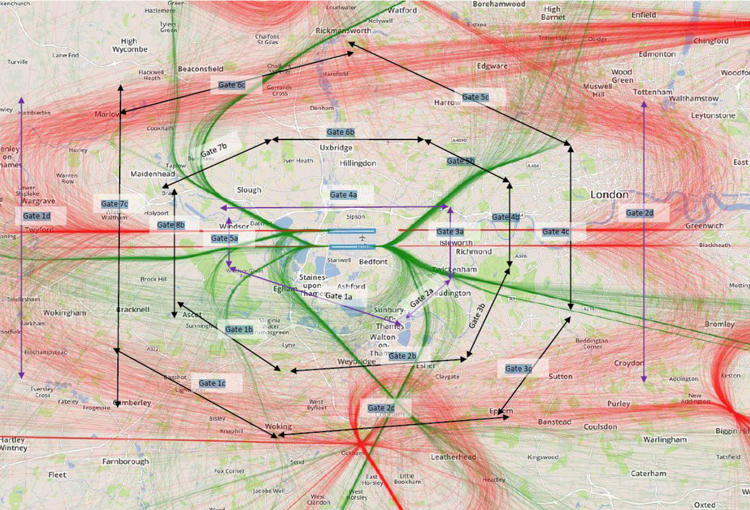

Community efforts to shape Heathrow’s airspace have been lead by the Heathrow Community Noise Forum (HCNF). The forum has begun analyzing the Heathrow airspace using a series of penetration gates (fig. 2) that depict aggregate flight paths over strips of land. The strips of land represent particularly sensitive areas, chosen by community members, with a view to ultimately better control noise in these areas. While the gates are currently used only to analyze flight distribution over the territory, they have potential to be used as a policy tool for shaping airspace relative to specific territorial zones. A series of gates could be used not only to describe the historical airspace, but also in negotiations over a specific shape for the government’s proposed noise envelope. Taken together HCNF’s analytic efforts and Heathrow’s flight-control experiments could contribute to a holistic planning strategy that re-engages the problem of aviation noise in the Heathrow territory’s open space.

Heathrow’s noise landscape will remain contentious for the foreseeable future. The prospect of a third runway, which would destroy the villages north of Bath Road, is enough to enrage members of the local communities for many years. In spite of this threatened land-grab many local residents also rely on the airport for their livelihoods and view its closeness as a convenience. Furthermore, the economy of Greater London is heavily reliant on Heathrow for its connectivity to the wider world. In this complex political ecology new techniques of measuring the noise landscape and sharing data are bringing about small but significant changes. We have seen how access to data on noise and flight paths has given local communities greater leverage in negotiation, allowing them to better articulate their grievances and their demands. Additionally, the airport today has greater control than ever over the routing of flights over the territory, and increasing motivation to act transparently and cooperate with local communities over airspace planning. The production of data, its visualization and its dissemination are driving these changes and creating opportunity for more equitable policy that takes into account aspects of the noise landscape that could neither be measured nor coordinated in the past. The history of Heathrow’s noise landscape suggests that these hopeful developments should be accompanied by skepticism of the potential biases of data and of its use as a tool to legitimize the status quo. If the bigness of noise data can be matched by the broadness of its distribution it can be a fertile ground for new ideas, new solutions, and the dissolution of old oppositions. Openly collected and distributed data about the noise landscape is the necessary base condition for negotiating a better solution to the problem of noise at Heathrow- a solution that can address the urban realm instead of abandoning it.

[1] K. Bijsterveld, Mechanical Sound: Technology, Culture, and Public Problems of Noise in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2008), 196-197.

[2] M. Goldsmith, Discord : The Story of Noise. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 203.

[3] Committee on the Problem of Noise, Noise: Final Report, (London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1963), p.65, s.260.

[4] Ibid. p.65, s.261.

[5] Ibid. p.63, s.250, Table X.

[6] Ibid. p.74, s.299.

[7] Ibid. p.75, s.302.

[8] Ibid. p.65-66, s.262-265.

[9] Ibid. p.76, s.305.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid. p.78, s.317.

[13] Ibid, p.75, s.303.

[14] Goldsmith, Discord, op. cit. (note 2), 249.

[15] Department for Transport, Aviation Policy Framework (London, The Stationery Office, 2013), p.58, s.3.19. Online. Available HTTP:https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/153776/aviation-policy-framework.pdf

[16] Ibid. p.62, s. 3.33

[17] Teddington Action Group, Complaining, Online. Available HTTP: http://www.teddingtonactiongroup.com/complaining/ (accessed 10 October 2016)

[18] FlightRadar24, How it Works, Online. Available HTTP: https://www.flightradar24.com/how-it-works (accessed 10 October 2016)

[19] Committee on the Problem of Noise, Noise: Final Report, op. cit. (note 3), p.67, s.271

[20] Netherlands Aerospace Centre, Verification of Heathrow Noise and Track Keeping Systems, Online. Available HTTP: http://www.heathrow.com/file_source/HeathrowNoise/Static/NLR-CR-2016-089.pdf (accessed 10 October 2016), p.5, s.1.

[21] J. Ungoed-Thomas and M. Woolf, ‘Revealed: The Plot to Expand Heathrow’, Sunday Times (London), 9 March 2008

[22] Airports Commission, Final Report (London, The Stationery Office, July 2015), p.303, s.14.94. Online. Available HTTP: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/airports-commission-final-report (accessed 10 October 2016)

[23] J. Stewart and A. Bronzaft, Why noise matters : A worldwide perspective on the problems, policies and solutions. (London, Earthscan, 2011), 52-56.

[24] London Borough of Hounslow, Open Space Strategy: Final Draft, April 2013 Online. Available HTTP: http://www.hounslow.gov.uk/london_borough_of_hounslow_-_open_space_strategy.pdf (accessed 10 October 2016), p.6-7, s.1.14.

[25] R. Cadbury, ‘Ruth Cadbury: Adobe Outdoor Classroom – Not an Igloo!’ 6 June 2011. Online. Available HTTP : http://ruthcadbury.blogspot.com/2011/06/adobe-outdoor-classroom-not-igloo.html (accessed 10 October 2016).

[26] P. Cerar, ‘Heathrow Noise Hinders Pupils Reading Progress’, London Evening Standard (London), 28 March 2013. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.standard.co.uk/news/transport/heathrow-noise-hinders-pupils-reading-progress-8552639.html (accessed 10 October 2016).

[27]G. Topham, ‘Heathrow Pays £1.8m for Adobe Huts to Protect Pupils’ Ears from Aircraft Noise.’ The Guardian (London), 8 November 2013. Online. Available HTTP: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/nov/08/heathrow-school-adobe-huts-protect-pupils-hearing (accessed 10 October 2016).

[28]Airports Commission, Final Report, op. cit. (note 22), 278.

[29]Anderson Acoustics, Westerly and Easterly Departure Trials 2014- Noise Analysis & Community Response, July 2015. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.heathrow.com/file_source/HeathrowNoise/Static/Noise_impacts_Community_Response_easterly_and_westerly_trials_2014.pdf, 34 (accessed 10 October 2016).

[30]BBC News, ‘Heathrow Airspace Trials: Life under the Flight Path’, 12 November 2014 Online. Available HTTP: http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-29597561 (accessed 10 October 2016).